Landano has been conducting pilot projects in rural Ghana and Mozambique to drive the requirements and design of our Minimum Viable Product (MVP) software release.

We believe that technology for its own sake is a lost opportunity, and that land administration projects designed and built without first understanding the socio-cultural context in which they will be deployed are inevitably limited in their ability to spark societal change and improvement.

Instead, development must be informed by an on-the-ground understanding of the people, their culture, and the systems the technology is designed to interact with. This principle continues to guide our activities in Ghana, Mozambique, and is now being applied in our project’s approach to land right issues in Kenya.

The Landano difference

Over the last two centuries, the relationship between land and people has become increasingly influenced by the desire to leverage it for economic development.

However, this commodification of land is challenged by historically held perspectives that see the relationship between humans and land as a continuum– one that connects us to the sacred world. In many communities in sub-Saharan Africa, land as a resource is held communally with the intention of leveraging it for more than just personal and economic gain.

Landano is not trying to replace centralized government registry functions or force marginalized people to accept European systems and norms. Rather, Landano is providing a world-class, user-driven technology platform that enables the continuation and prosperous evolution of the types of traditional land rights practices that have been in place in Sub-Saharan Africa for millennia. Wherever possible, we leverage favourable land right legislation.

Creating standards-compliant records for previously undocumented but constitutional land rights is the key distinguishing feature of the Landano solution that sets it apart from prior, unsuccessful attempts to use blockchain technology for land registration (e.g. see Anash, 2023).

After achieving independence from their European colonizers, both Ghana and Mozambique enacted new constitutions that recognize the authority of traditional leaders, like village chiefs and family heads. These leaders make authoritative decisions on their community’s behalf about how their land is used.

These countries enjoy a “pluralistic” legal system which attempts to marry traditional land right practices with the more bureaucratic cadastral systems put in place by their European colonizers.

This has not been an easy integration. Traditional rights all too often fall victim to predatory practices of political and social elites who exercise their control and privilege within the centralized cadastral system and its technology-intensive components. Landano is giving traditional communities a fighting chance by leveling the playing field. Our world-class recordkeeping system is compliant with international standards and national laws.

However, it is also simple enough to be accessed by users with limited literacy or digital experience. Better yet, the land right records it generates can be leveraged to open up previously inaccessible lending and financial opportunities by safeguarding land right transactions. One of these opportunities, which we are assessing now, is to connect our users to DeFi microfinance opportunities on the Cardano blockchain.

Landano is positioning itself to be a world-wide land administration solution, to bring land tenure security and new financial opportunities wherever they are needed. We have been looking beyond Ghana and Mozambique to expand into jurisdictions with similar histories and opportunities. Of course, Africa is a rich and complex continent with many different cultures, languages, and norms. This holds true for land management as well. What may be applicable in one location may not be valid elsewhere, whether in another nation state or in another village.

Therefore, it is important to establish a sound understanding of the socio-juridical history of a particular region before attempting to introduce new systems. One of our pilot project deliverables is a way to incorporate such context into a jurisdiction/internationalization template to port the Landano technology to new markets.

Land administration in Kenya

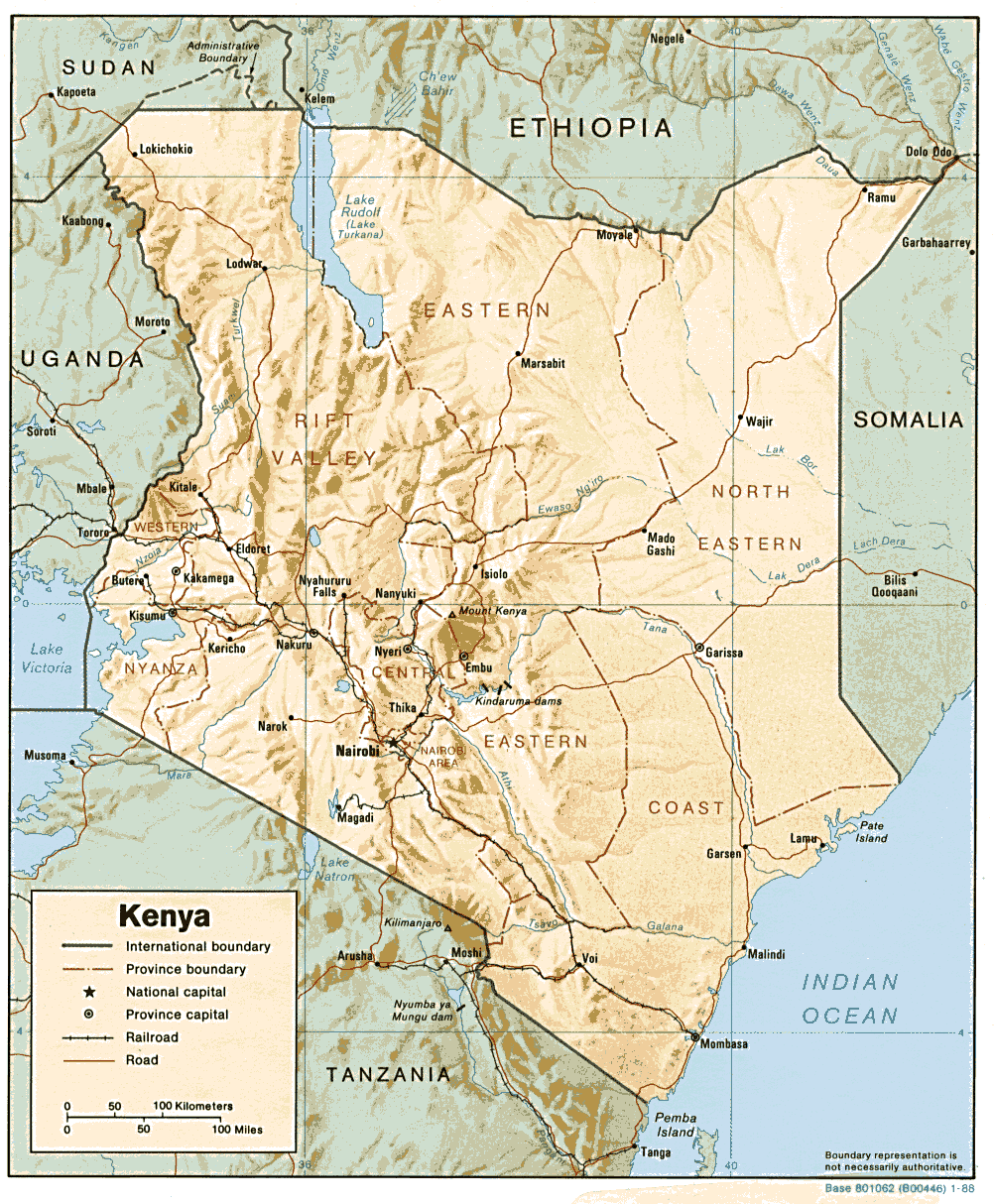

Kenya is an East African country with an incredibly diverse population of over 53 million people that represent many of the continent’s major ethno-racial groups including the Bantus, Nilotic, and Cushitic peoples. In fact, the country’s most recent population and housing census recognized 45 different ethnicities residing in Kenya (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The Bantu-speaking ethnic groups make up about 60%, Nilotic-speaking ethnic groups make up about 30%, Cushitic ethnic groups covering another 9%, and less than 1% of the population consists of citizens of European, Middle Eastern, and Asian descent.

Each of these individual ethnic groups, within broad linguistic groupings, had (and still have) their own unique relationships with land. These are influenced by a variety of factors, including societal traditions, the seasons, or topographic features in the surroundings. Communities from the same ethnic groups can even differ in these relationships; for example, Bantu-speaking ethnic groups living near bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, or the Indian Ocean, differ in how they relate to the land than other Bantu-speaking ethnic groups. However, what they have in common is that each of these groups has historically held land communally and allocated resources within the community as needed. This changed with colonization in the 19th century, and the impact of this shift dramatically changed the varied relationships held between humans and land across Kenya.

Land Administration under the British

Almost immediately after the Imperial British East Africa Company first arrived in Kenya in 1888, the British elite began to seize the land which they assessed as having future economic value. In order to formalize their right to these lands, the British Crown enacted an ordinance in 1902 known as the Registration of Documents CAP 285 (Kenya, 2022) which effectively replaced traditional land administration systems with one that favored the colonizers. In 1920, Kenya was annexed as a British Dominion and became known as the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. More land was taken and reserved for settlers.

With the need to allocate and sell land, additional statutory instruments were enacted to support these processes. Land administration activities such as cadastral mapping were carried out to transform land from communal assets to the statutory freehold for individual ownership. Both the Land Consolidation Act CAP 283 (2022) and the Survey Act CAP 299 (2022) were enacted for the consolidation of small plots of land with communal ownership into larger parcels geared towards economic activities (Siriba, 2011).

These legislative instruments influenced land administration policies for almost five decades [10, 13]. The communities that had traditionally lived in what were soon termed “White Highlands”, or high-value agricultural land, were systematically disenfranchised in favor of settlers from the UK and South Africa. This disregard for traditional perspectives on land administration combined with the denial of other freedoms lead to the earliest anti-colonial movements such as the Nandi resistance at the end of the 19th century (Gold, 1978) and the Mijikenda resistance of the early 20th century (Carrier et al., 2016). Eventually, armed conflict resulted in the death of over 100,000 Kenyans and another 1.5 million (almost 20% of the total population) were forced through a system of detention camps and secured villages (Elkins, 2005).

Despite the brutal subjugation, Kenya gained its independence in 1963. The new state had to reckon with the challenge of reshaping the land administration system which had been imposed on them. The country wanted a system more closely aligned with traditional understandings of human relationships to land, but also desired to modernize the country to benefit its citizens. Several laws were ratified in an effort to formalize customary rights. Of these, land adjudication was the main land tenure reform carried out after independence and was meant to secure customary rights of indigenous people by issuing land titles (Siriba et al., 2011:179). However, many of the existing legal instruments used in this process were still artifacts from colonization and proved unsuccessful in their task.

In 2010 Kenya established a new constitution (Boone et al., 2016, Hofman and Katuu, 2022), and it made two significant changes in land administration: first, it decentralized governance across 47 new county governments which were tasked with the responsibility of managing their jurisdictions; second, Article 162(2)(b) established a superior court known as the Environment and Land Court to aid in dealing with the large number of land related legal disputes.

Over the years, a number of other legal instruments were established to help unravel the complexities of Kenyan land rights. However, success has only ever been partial as many of the laws from previous governments still impact the land administration system today (Karoney, 2021a, Karoney, 2021b, Omondi, 2018).

Where Landano Fits In

What many have seen as merely a technical problem concerning land administration in Kenya has instead been revealed as a highly nuanced issue of varied perspectives, values, and beliefs concerning the relationship between people and the land that they reside on. Because of these myriad perspectives, unilateral attempts to solve the land administration issues through legislative change have at best been inconsistent, at worst they have failed to wholly address the underlying issues.

Colonial law designed systematic methods for the disenfranchisement of indigenous communities in order to transform land as a communally shared resource into a financial asset. Post-colonization, political elites who may have reversed such mechanisms instead profited by embedding them further. The result of which has been persistent ideological problems within land administration.

The nuanced complexity of Kenya’s land administration reveals the need for a different strategy. Where centralized top-down approaches have failed to wholly address user needs, we believe that the Landano approach used in our other pilot countries also has value in Kenya. Local partnerships and community leader buy-in allows our technology to work for our users. Instead of building systems to replace traditional forms of land administration, our approach is to partner with communities to manage their resources in a manner respectful of their cultural ideals while ensuring best-practice compliance with regulatory and record-keeping requirements. We deliver this on a decentralized, self-sovereign platform that connects our users to to new financing opportunities.

We appreciate that this requires significant work, and that it won’t be easy. But where other solutions have neglected due diligence, we take the time to understand what land means to the communities we seek to partner with. And this creates meaningful change.\

References

A. (2016), Land politics under Kenya’s new constitution: counties, devolution, and the National Land Commission. Working Paper Series.

Ansah, Barikisa Owusu, Winrich Voss, Kwabena Obeng Asiama, and Ibrahim Yahaya Wuni. 2023. “A Systematic Review of the Institutional Success Factors for Blockchain-Based Land Administration.” Land Use Policy 125 (106473).

Boone, C., Dyzenhaus, A., Ouma, S., Owino, J. K., Gateri, C. W., Gargule, A., Klopp, J. & Manji,

Carrier, N. and Nyamweru, C. Reinventing Africa’s national heroes: The case of Mekatilili, a

Elkins, C. Imperial Reckoning: The untold story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. Macmillan, New York, 2005.

Gold, A. E. The Nandi in transition: background to Nandi resistance to the British 1895-1906.

Hofman, D. & Katuu, S. (2022), Law and recordkeeping in four African countries: Botswana, Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe. In: NGOEPE, M. (ed.) Management of digital records in Africa. Oxon, UK: Routledge, pp. 7-48.

Karoney, F. (2021a), Interview - Cabinet Secretary Karoney on Ardhisasa and Sectional Property Act [Online]. NTV Kenya. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrrkxdYPgDs [Accessed 10th July [2022].

Karoney, F. (2021b), Interview - Cabinet Secretary Karoney on Cleaning Kenya’s Land Registry [Online]. Nairobi: SpiceFM. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rj6Hea7SfAM [Accessed 10th July [2022].

Kenya Historical Review, 6, 1-2 (1978), 84-104.

Kenya. “Registration of Documents CAP 285.” Retrieved 28th September, 2022, from http://kenyalaw.org:8181/exist/kenyalex/actview.xql?actid=CAP.%20285, (1901).

Kenya. “Land Consolidation Act CAP 283.” Retrieved 28th September, 2022, from http://kenyalaw.org:8181/exist/kenyalex/actview.xql?actid=CAP.%20283, (1959).

Kenya. “Survey Act CAP 299.” Retrieved 28th September, 2022, from http://kenyalaw.org:8181/exist/kenyalex/actview.xql?actid=CAP.%20299, (1961).

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. “Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume IV: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics.” Retrieved 28th September, 2022, fromhttps://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro=2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-iv-distribution-of-population-by-socio-economic-characteristics&wpdmdl=5730&ind=7HRl6KateNzKXCJaxxaHSh1qe6C1M6VHznmVmKGBKgO5qIMXjby1XHM2u_swXdiR (2019).

Kenyan popular heroine. African Affairs, 115, 461 (2016), 599-620.

Maloba, W. O. Mau Mau and Kenya: an analysis of a peasant revolt. East African Publishers, Nairobi, 1994.

Omondi, D. (2018), Karoney sets up task force to guide on digitisation [Online]. Available: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/article/2001291085/karoney-sets-up-taskforce-to-guide-digtisation [Accessed 10th July 2022].

Siriba, D. N., Voß, W. and Mulaku, G. C. The Kenyan Cadastre and Modern Land Administration. Fachbeitrag, 136, 3 (2011), 177-186.