Landano is a decentralized application (dApp) that mints land right records as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) on the Cardano blockchain. Landano works in compliance with international record-keeping standards and local land laws. The goal is to enable new decentralized finance (DeFi) opportunities for formerly undocumented rights-holders.

To this end, we have been conducting a Landano pilot project in rural Ghana for the past few months. Ghana is a West African country that is home to approximately 31 million people, and is rich in coastal savannahs, tropical rain forests, and natural resources.. Ghana has been one of the more stable and democratic countries in the region. It has played a major role in inter-continental trade for many centuries and was the first sub-Saharan country to gain its national independence.

A quick history of land tenure in Ghana

Before colonial rule in Ghana, land was governed by customary law, which means that lands are held in trust and governed by traditional leaders, chiefs, and clans on behalf of their people. In this tradition, land is a spiritual and physical embodiment of the people who reside on it. It is regarded as an immortal entity.

These lands, depending on where you are in Ghana, are still known today as stool, skin, clan, and family lands and they make up about 80% of all land in Ghana. In all cases, these lands are held by their respective authority for the community. Those receiving rights in these lands don’t actually own their land outright but lease them from the customary authority who holds the interest. The remaining 20% are lands owned or managed by the state.

Since its independence, Ghana has attempted to create a land tenure system that can honour the traditional cultural land tenure practices while simultaneously implementing processes and records that are more aligned with the British legal system introduced during colonial rule.

This awkward marriage has resulted in an inefficient mix of centralized modernization initiatives that are tied to federal taxation schemes. These bump up against long-standing cultural traditions that favour more decentralized land allocation and community-driven resource prioritization.

The issues with the current system

The two land administration systems within Ghana do not communicate well with each other. Traditional processes are necessary to acquire land rights on the majority of land in Ghana. However, the state system does not formally recognize the records generated by those processes. Instead, the responsibility falls to the individual to navigate these complex systems and complete the necessary steps to satisfy both.

For example, a villager may approach their chief and acquire the rights to farm a parcel of their community’s customary land. This right takes the form of a lease and allows the villager to develop and benefit from the land for the duration of that lease.

However, while the villager may have been issued documentation of their transaction by the chief, the land administration did not receive any record of it. The responsibility falls on that individual to formalize, or “perfect”, their land rights by following a series of steps:

- acquiring necessary documentation from their customary authority,

- hiring a surveyor to establish their land boundaries,

- hiring a lawyer to submit the legal documentation,

- paying various administrative fees

- paying for travel costs if any of these steps are outside of their immediate community, which they often are

Whether the steps are too many, the time required too great, or simply because it costs too much, current research has clearly shown that many Ghanaians go without formally registering their land rights with the state. However, without formal registration, landowners are vulnerable to various land tenure risks, such as land encroachments, multiple sale of land parcels, and competing interests in land.

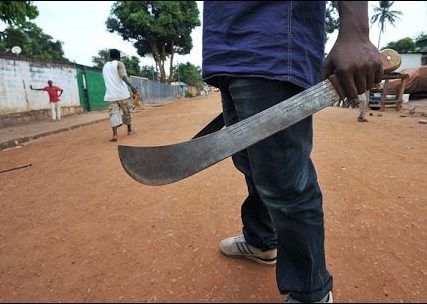

This has led to a high number of land tenure disputes in Ghana. Amazingly, 60% of all court cases in Ghana are related to land disputes. These often take years to settle and the original land rights holder often does not win their case due to bureaucratic, record-keeping idiosyncrasies. Those unable to pursue legal aid, or those who find the wait untenable, often resort to violent confrontations in order to protect their land rights.

The burden that these issues place on the citizens of Ghana has been characterized as a leading contributor to the country’s inability to improve critical infrastructure.

Ghana is not the only country struggling with improving its land registry systems. Many hundreds of millions of dollars of international development funding has been made available over recent decades to modernize and digitize land administration systems in the Global South.

Too often, these projects are driven by a top-down, centralized systems implementation paradigm that attempts to deploy architectures and practices that are in place in the Global North. They have not been sufficiently informed by a bottom-up understanding of customary land tenure practices.

This is clearly the case in Ghana where the current regulations are inadequate for capturing all of the various customary transactions that take place prior to entries, if any, into the federal Land Commission system.

A bridge between systems

Landano wants to provide technology and services to address this gap. We are not attempting to replace or bypass existing federal registry systems. Landano wants to be the bridge between customary and state land tenure processes, safeguarding authentic land rights and improving the reliability of land administration records.

Landano offers a way for chiefs to issue their land rights documents more efficiently and more reliably while providing a central transaction database. For land rights-holders, Landano safeguards their records and establishes a timeline which points to the rightful owner and their progress through the land administration system.

We launched a pilot project in the township of Hiawu Besease, in Ghana’s Ashanti region. Landano team members are working closely with village leadership to create digital records to support their land administration functions.

The Landano architecture is designed to comply with the Ghana Lands Act, Ghanaian digital evidence requirements, and international ISO standards for record-keeping. It supports use cases for land administrators, rights-holders, and rights-seekers.

Landano creates and archives a key set of records that are critical to traditional land right allocation practices, namely:

- land parcel surveys and site plans with map plots

- audio-visual recordings of land right allocations by community leaders

- allocation note records

- indenture documents

- lease contracts

Landano also creates a Cardano non-fungible token (NFT) for each land parcel and each corresponding land right document. The supporting digital files for each NFT are stored as a standards-compliant archival package on the Arweave decentralized storage platform.

Landano provides a convenient web and smartphone interface to create and retrieve these records, including geospatial cadastral data associated with each land parcel. However, the system is truly decentralized in the sense that all records can be accessed directly via Cardano and Arweave nodes and block explorers, independently from Landano.

Landano is designed to connect records generated through the traditional land allocation processes with the federal Land Commission system and the corresponding registration or “perfection” procedures. However, whether the Landano user decides to complete this formalization stage or not, the Landano records themselves serve as trustworthy artifacts of the constitutional land allocation decisions made by community leaders.

The end goal

The Landano goal is to structure these records in such a way that they can be used for decentralized finance (DeFi) services so that Landano users can leverage their land right records for financing opportunities like mortgages and business loans. We are working with collaborators in the Cardano ecosystem to provide these services.

In the meantime, we are busy in Hiawu Besease to complete this land right use case from start to finish. We are preparing to issue a full set of land right records for five land parcels in our pilot project scenario. We look forward to sharing the outcome of this work in an upcoming post.

References

Ghana-Land Act, 1036. 2020.

| Imani Center for Policy and Education. 2020. “Addressing the Challenges to Property Registration in Ghana | Imani.” IMANI Center for Policy and Education. https://youtu.be/a_YPf8hv-Mg. |

| Koku Avle, Bernard. 2021. “Effective Land Administration in Ghana | Point of View.” CitiTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=50tJkE86CY4. |

Mintah, Kwabena, Festival Godwin Boateng, Kingsley Tetteh Baako, Eric Gaisie, and Gideon Kwame Otchere. 2021. “Blockchain on Stool Land Acquisition: Lessons from Ghana for Strengthening Land Tenure Security Other than Titling.” Land Use Policy 109 (October): 105635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105635.

Pomevor, S M. 2021. “Mobilisation of Stool Land Revenue for the Development of Local Economies: The Prospects and Challenges.” Local Development & Society, June, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2021.1944287.

Shem, Shemcy. 2018. “Customary Land Tenure System in Ghana and Its Problems.” September 29, 2018. https://yen.com.gh/111693-customary-land-tenure-system-ghana-problems.html.